Through-and-through abdominal gunshot wound in a patient with acute alcoholic hepatitis

Written by Tobias Haltmeier

Category

Published 29 October 2013

Tobias Haltmeier, MD, Guido Beldi, MD, Beat Schnüriger, MD

All at the Department of Visceral and Transplant Surgery, Bern University Hospital, Bern, Switzerlan

Background

Abdominal gunshot wounds (GSW) may lead to massive intra-abdominal bleeding and require prompt diagnostic workup and surgical treatment. However, the initial clinical evaluation of abdominal GSW can be challenging.[1-4]

Trauma in patients with impaired liver function, such as liver cirrhosis or hepatitis, is associated with increased mortality, due to haemorrhagic and pulmonary complications. These patients warrant aggressive monitoring and prompt surgical intervention if indicated.[5-7]

Up-to-date management of trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) includes damage control surgery, minimally invasive angioembolization of bleeding arteries, early substitution of packed red blood cells (PRBC), fresh frozen plasma (FFP) and platelet concentrates (PC), as well as correction of hypothermia and acidosis.[8-10] There is currently a trend towards point-of-care use of coagulation factor concentrates.[11-14]

We report the case of a patient with an abdominal gunshot wound and acute alcoholic hepatitis, leading to critical trauma-induced haemorrhage and coagulopathy requiring massive transfusion.

Case

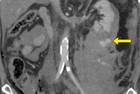

A 57 year old patient was admitted to the emergency room (ER) of Bern University Hospital with an abdominal GSW in a suicide attempt under the influence of alcohol. Initially the patient was haemodynamically stable, awake and alert. There were two gunshot wounds, one in the left upper abdomen, the other dorsal in the left upper flank. (Figure 1) Generalized tenderness of the abdomen was present. FAST showed a little free fluid in the left upper abdomen and the Douglas space. Damage control laparotomy was performed, revealing small bowel perforation, transverse colon mesentery perforation with active bleeding, active bleeding from the left retroperitoneal (zone 2) bullet tract with haematoma and grade 2 laceration of the lower pole of the left kidney. Segmental small bowel resection with primary anastomosis, left intra-abdominal packing and a liver biopsy were performed. The left sided retroperitoneal haematoma was not opened and explored during the primary operation.

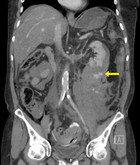

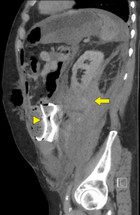

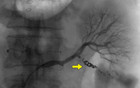

Immediate postoperative abdominal angio-CT scan revealed ongoing active bleeding from the lower pole of the left kidney. (Figures 2 and 3) Angiography with selective coiling of the corresponding segmental artery was performed (Figures 4 and 5) and the patient was transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU). Overall, the patient required transfusion with 24 PRBC, 24 FFP and 3 PC. However, blood coagulation remained poor (Figure 6) despite the repeated administration of recombinant factor VIIa (Novoseven®), fibrinogen, tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron®) and calcium. The abdominal drains continued to drain 300-600 ml of blood per hour and the patient deteriorated haemodynamically. Therefore, second look laparotomy with complete mobilization of the left kidney, left retroperitoneal packing and open abdomen negative pressure therapy were performed.

Histopathology of the liver biopsy showed high grade alcoholic steatohepatitis with portal fibrosis. Child-Pugh score was B (9 points), MELD was 23 points. Abdominal negative pressure therapy (ABThera™, KCI) revealed 200-300ml of bloody ascites per hour and the patient required ongoing blood component transfusion. Nevertheless, 2 days after the initial trauma, the patient was haemodynamically stable. Third look laparotomy with removal of the packs and intraperitoneal onlay mesh (IPOM) repair of the open abdomen with negative pressure therapy on top of the mesh was performed, greatly reducing blood drainage.

Subsequently the patient developed severe delirium tremens, most likely due to the pre-existing alcohol and benzodiazepine abuse. Delirium tremens was controlled with haloperidol and diazepam. On hospital day 14, the patient was transferred to a regional hospital. The further clinical course was complicated by respiratory failure due to atelectasis and subsequent non-invasive ventilation in the ICU of the regional hospital.

Discussion

Abdominal GSW warrant prompt diagnostic workup and treatment. Emergency laparotomy is indicated if shock, evisceration or signs of peritonitis are present.[1] However, not all abdominal GSW require immediate laparotomy. In asymptomatic and stable patients, abdominopelvic CT scan is performed. Tangential GSW in patients without peritoneal signs are treated conservatively with close clinical follow up. Stable patients with isolated solid organ injuries may be managed conservatively, provided that a full time interventional radiology and trauma surgery service is available. In case of haemodynamic deterioration or peritonitis, prompt surgical or interventional treatment is needed. [2-4, 15]

Zone 2 retroperitoneal haematomas are managed conservatively in stable patients without signs of active bleeding. In unstable patients and if active bleeding is present, zone 2 retroperitoneal haematomas should be opened and explored. This is especially the case after penetrating trauma.[16-19] In the current case, the retroperitoneal haematoma was not opened and packed during the first intervention, leading to persistent retroperitoneal bleeding, even after angiography and coiling of the injured left lower pole renal artery. However, sufficient haemostasis and stabilization of haemodynamics were achieved after second-look laparotomy, with full mobilization of the left kidney and retroperitoneal packing. (Figure 3)

Liver cirrhosis and impaired liver function are independent risk factors for increased mortality and more frequent complications in trauma patients.[6] Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), trauma-induced coagulopathy (TIC) and septic complications are associated with liver cirrhosis in trauma patients. These patients warrant aggressive surgical and medical treatment, as well as close monitoring.[5, 7]

TIC is associated with depletion of coagulation factors I, II, V, VII, VIII, IX and X and activation of the anticoagulant Protein C pathway.[20] Timely diagnosis and correction of the underlying factors, such as hypothermia and acidosis, as well as substitution with PRBC, FFP and PC, are crucial in the early treatment of TIC.[8, 9] Hypovolaemia should not be treated with infusion of crystalloids or colloids, to avoid haemodilution with further aggravation of TIC.[21, 22] Surgery is limited to damage control, in order to avoid additional trauma and blood loss.[9] Individualized treatment of TIC using coagulation factor concentrates such as fibrinogen, prothrombin complex concentrates or recombinant coagulation factors (VII and XIII) is currently being discussed.[9, 14, 23] Use of coagulation factors and factor concentrates may reduce the need for PRBC, FFP and PC.[10] Viscoelastic tests (thromboelastometry, thromboelastography) are increasingly being used to detect TIC and to guide point-of-care haemostatic therapy, i.e. the application of the above mentioned coagulation factor concentrates.[12, 24] However, such transfusion therapy needs to be investigated in future prospective studies.[13]

Conclusion

In the case presented, impaired liver function caused prolonged TIC, despite the adequate massive transfusion of blood products and substitution of artificial coagulation factors. Therefore, optimal surgical and interventional control of haemorrhage and close monitoring are mandatory in trauma patients with impaired liver function.

Bibliography

- Biffl WL, Moore EE: Management guidelines for penetrating abdominal trauma. Current opinion in critical care 2010, 16(6):609-617.

- Inaba K, Branco BC, Moe D, Barmparas G, Okoye O, Lam L, Talving P, Demetriades D: Prospective evaluation of selective nonoperative management of torso gunshot wounds: when is it safe to discharge? The journal of trauma and acute care surgery 2012, 72(4):884-891.

- Inaba K, Demetriades D: The nonoperative management of penetrating abdominal trauma. Advances in surgery 2007, 41:51-62.

- Lamb CM, Garner JP: Selective non-operative management of civilian gunshot wounds to the abdomen: A systematic review of the evidence. Injury 2013.

- Talving P, Lustenberger T, Okoye OT, Lam L, Smith JA, Inaba K, Mohseni S, Chan L, Demetriades D: The impact of liver cirrhosis on outcomes in trauma patients: A prospective study. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery 2013, 75(4):699-703.

- Georgiou C, Inaba K, Teixeira PG, Hadjizacharia P, Chan LS, Brown C, Salim A, Rhee P, Demetriades D: Cirrhosis and trauma are a lethal combination. World journal of surgery 2009, 33(5):1087-1092.

- Demetriades D, Constantinou C, Salim A, Velmahos G, Rhee P, Chan L: Liver cirrhosis in patients undergoing laparotomy for trauma: effect on outcomes. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 2004, 199(4):538-542.

- Lier H, Bottiger BW, Hinkelbein J, Krep H, Bernhard M: Coagulation management in multiple trauma: a systematic review. Intensive care medicine 2011, 37(4):572-582.

- Schochl H, Grassetto A, Schlimp CJ: Management of hemorrhage in trauma. Journal of cardiothoracic and vascular anesthesia 2013, 27(4 Suppl):S35-43.

- Zentai C, Grottke O, Spahn DR, Rossaint R: Nonsurgical techniques to control massive bleeding. Anesthesiology clinics 2013, 31(1):41-53.

- Fries D: The early use of fibrinogen, prothrombin complex concentrate, and recombinant-activated factor VIIa in massive bleeding. Transfusion 2013, 53 Suppl 1:91S-95S.

- Godier A, Susen S: Trauma-induced coagulopathy. Annales francaises d'anesthesie et de reanimation 2013, 32(7-8):527-530.

- Grottke O: Coagulation management. Current opinion in critical care 2012, 18(6):641-646.

- Sorensen B, Fries D: Emerging treatment strategies for trauma-induced coagulopathy. The British journal of surgery 2012, 99 Suppl 1:40-50.

- Como JJ, Bokhari F, Chiu WC, Duane TM, Holevar MR, Tandoh MA, Ivatury RR, Scalea TM: Practice management guidelines for selective nonoperative management of penetrating abdominal trauma. The Journal of trauma 2010, 68(3):721-733.

- Madiba TE, Muckart DJ: Retroperitoneal haematoma and related organ injury--management approach. South African journal of surgery Suid-Afrikaanse tydskrif vir chirurgie 2001, 39(2):41-45.

- Feliciano DV: Management of traumatic retroperitoneal hematoma. Annals of surgery 1990, 211(2):109-123.

- Maull KI, Rozycki GS, Vinsant GO, Pedigo RE: Retroperitoneal injuries: pitfalls in diagnosis and management. Southern medical journal 1987, 80(9):1111-1115.

- Costa M, Robbs JV: Management of retroperitoneal haematoma following penetrating trauma. The British journal of surgery 1985, 72(8):662-664.

- Cohen MJ, Kutcher M, Redick B, Nelson M, Call M, Knudson MM, Schreiber MA, Bulger EM, Muskat P, Alarcon LH et al: Clinical and mechanistic drivers of acute traumatic coagulopathy. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery 2013, 75(1 Suppl 1):S40-47.

- Shaz BH, Winkler AM, James AB, Hillyer CD, MacLeod JB: Pathophysiology of early trauma-induced coagulopathy: emerging evidence for hemodilution and coagulation factor depletion. The Journal of trauma 2011, 70(6):1401-1407.

- Sondeen JL, Prince MD, Kheirabadi BS, Wade CE, Polykratis IA, de Guzman R, Dubick MA: Initial resuscitation with plasma and other blood components reduced bleeding compared to hetastarch in anesthetized swine with uncontrolled splenic hemorrhage. Transfusion 2011, 51(4):779-792.

- Schochl H, Schlimp CJ: Trauma Bleeding Management: The Concept of Goal-Directed Primary Care. Anesthesia and analgesia 2013.

- Schochl H, Schlimp CJ, Voelckel W: Potential value of pharmacological protocols in trauma. Current opinion in anaesthesiology 2013, 26(2):221-229.

Comments