Blunt extraperitoneal rectal injury in combination with a pelvic fracture

Written by Jessica Laue

Category

Published 19 April 2012

Laue J, MD; Kernig K, MS; Banz V, MD; Keel M, MD; Schnüriger B, MD

All Bern University Hospital

Introduction

Blunt rectal injury is a rare entity. The vast majority of published cases involve patients suffering from penetrating mechanisms of trauma, making any conclusions or recommendations for the treatment of such blunt injuries difficult. Here, we present a patient, who sustained a blunt extraperitoneal rectal injury in combination with a pelvic fracture arising from a fall off a horse.

Case Report

A 60-year-old, otherwise healthy male sustained a fall from a horse. The exact mechanism of the accident remained uncertain. The patient was immediately admitted to a regional hospital.

He was hemodynamically stable on admission and the initial pelvic x-ray showed a type B fracture with a longitudinal fracture of the sacrum involving the neuronal foramina. In addition, the patient had an open right lower extremity fracture. The FAST was negative but digital rectal examination revealed the presence of blood. After confirming hemodynamic stability the patient was air-lifted to the Emergency Department of Berne University Hospital.

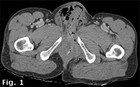

Upon admission a contrast-enhanced computed tomography scan showed emphysematous soft tissue at the level of the symphysis, which extended down to the scrotum and penis root (CT, Fig. 1, 2).

There was also free air in the extraperitoneal, perirectal space (see CT scan, Fig.3). A rectal perforation with leakage of air into the surrounding soft tissue was suspected and confirmed by rectal administration of contrast agent. There was no free abdominal fluid or air and solid organ lesions could be excluded. In addition, a lesion of the ureter was excluded by ureterography (Fig. 4).

Diagnostic laparoscopy performed on the same day confirmed the absence of any associated abdominal injuries and a laparoscopically-assisted diverting sigmoidostomy was successfully carried out. Intraoperative rectoscopy confirmed a 3 cm-long, longitudinal anterior rectal laceration ending at the distal mid third of the rectum. The rectum was washed out to remove any fecal matter and the laceration left open. In addition the open book fracture of the pelvis was stabilized by an external fixator and the extremity fracture stabilized with a tibial pin (Fig.5a + 5b).

On hospital day 2 the patient became increasingly septic (fever, decreased systolic blood pressure, and urine output) and the decision was made to take the patient back to theatre. A team consisting of an orthopedic and visceral surgeon performed a lower midline laparotomy with an anterior extraperitoneal access to the rectum and the retro-symphysal space. The pelvic ring was completely disrupted and the rectum and the muscles of the pelvic floor lacerated.

An infected hematoma was evacuated and bleeders from the retrosymphysal venous plexus were controlled. The rectal laceration was repaired in two layers from the anterior extraperitoneal approach as well as transanally. At the end of the operation, the perirectal space was extensively lavaged and a retrovesical drain inserted. The disrupted symphysis was brought into alignment using a cerclage. The sacral fracture was stabilized with an iliosacral screw, along a tension plate fixed to the third sacral vertebral body. On day 11, the symphyseal cerclage was removed and replaced by a plate osteosynthesis.

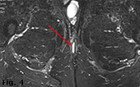

The further postoperative recovery was uneventful and the patient discharged on day 24. Subsequently, the patient was closely followed in the outpatient department. The tibial pin was dynamised on day 166 by removing both the distal and the proximal medial interlocking screw. Six and a half months after the initial trauma, an abscess was found at the scrotal root originating from an anterior trans-sphincteric fistula (Fig. 4). The abscess was excised and a penrose drain inserted into the fistula. In addition, an antibiotic regimen comprising of ciprofloxacin and metronidazol was administered for 14 days.

Two and a half months after initial abscess drainage (approximately nine months post-trauma) the trans-sphincteric fistula was resected and a mucosal flap was performed. The mucosal flap remained vital and the patient recovered well from the surgery. Transanal manometry and a pelvic MRI showed physiologic function of the sphincteric muscles and any residual infectious collections could be excluded. Closure of the protective sigmoidostomy was performed one year after accident.

Discussion

While the management of rectal injury has changed over the last few years, optimal treatment remains a matter of great debate. Unfortunately, there is only level III evidence regarding treatment of patients suffering from traumatic rectal injuries. In addition, most of the patients included in the studies sustained penetrating mechanisms of injury, making any conclusions on the treatment of patients with blunt mechanisms of injury even more debatable and uncertain.

Management strategies described in the literature include diverting sigmoidostomy, presacral drainage, direct suture repair of the rectal laceration and irrigation of the rectum. In 1989, Burch et al. recommended fecal diversion and presacral drainage for rectal injury management. Presacral drainage was believed to prevent perirectal infections due to fecal contamination. However, later studies showed that presacral drainage for penetrating rectal injuries does not positively influence the occurrence of local infectious complications. Furthermore, Navsaria and colleagues concluded from their retrospective review that extraperitoneal rectal injuries caused by low-velocity penetrating trauma could be treated by fecal diversion alone.

And yet, even fecal diversion in the management of rectal injuries has been questioned. In a study by Gonzales, fourteen patients suffering non-destructive penetrating extraperitoneal rectal injuries were treated without fecal diversion or direct suture repair. In none of these patients infectious complications occurred.

Prospective trials are needed to substantiate the theory of non-diversion- as well as non-repair management. Currently, an American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) funded multi-institutional study is ongoing to investigate the role of diverting sigmoidostomy in the management of patients sustaining extraperitoneal rectal injury (www.aast.org). In the current case report, a perineal fistula occurred as one of the common infectious complications after rectal injury. According to De Parades, the primary goal of fistula management is to control infection without sacrificing the anal continence. As antibiotics are not curative, but only constrain the extent of infection, more focus is put on operative interventions. While abscesses should be incised and drained, the dogma of fistula treatment is fistulotomy. Although fistulotomy has shown satisfying results, there remains the potential risk of affecting anal continence. This is why there is increasing interest in sphincter-sparing techniques, such as mucosal advancement flaps (as performed in our case), injection of fibrin glue or plug procedures.

Conclusion

In patients, where the magnitude of rectal injury is extensive or difficult to evaluate, fecal diversion, preferably by means of a loop sigmoidostomy, remains the preferred treatment of choice. Although the necessity to repair a rectal injury is still controversial, we believe that, provided the rectal injury can be visualized without extensive dissection, it should be directly repaired. Furthermore, especially in the presence of a concomitant pelvic fractures, it is crucial to exclude associated abdominal injuries, e.g. by diagnostic laparoscopy. This is ideally carried out in an interdisciplinary setting, including an orthopedic and visceral surgeon, allowing for simultaneous evaluation of the extraperitoneal rectum and stabilization of the anterior pelvic ring, performed through the same incision.

A selection of recommended articles:

- Gruden E, Ragot E, Arienzo R, Revaux A, Magri M, Grossin M, Leroy C, Msika S, Kianmanesh R. : Massive rectal bleeding distant from a blunt car trauma. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2010 Sep;34(8-9):499-501.

- Roy AK, Shukla P, Singh S. : Rectal perforation and evisceration of the small intestine: a rare injury in blunt trauma of the abdomen. J Trauma. 2009 Jan; 66(1):286.

- McClenathan JH, Dabadghav N. : Blunt rectal trauma causing intramural rectal hematoma: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 2004 March ; 47(3) :380-2.

- Soto LI 3rd, Saltzman DA : Rectal impalement a case review. Minn Med. 2003 April ; 86(4) :48-9.

- Fries J, Jensen AL, Hillmose LA : Perforation of the rectum – caused by blunt injury. Ugesker Laeger. 1998 Jan 19; 160(4):437-8.

- Jon M. Burch, M.D. David V. Feliciano, M.D., and Kenneth L. Mattox, M.D.: Colostomy and Drainage for Civilian Rectal Injuries: Is That All? Ann Surg. 1989 May; 209(5):600-10; discussion 610-1.

- Steinig JP, Boyd CR: Presacral drainage in penetrating extraperitoneal rectal injuries: is it necessary? Am Surg. 1996 Sep; 62(9):765-7.

- Gonzalez RP, Falimirski ME, Holevar MR: The Role of Presacral Drainage in the Management of Penetrating Rectal Injuries. J Trauma. 1998 Oct; 45(4):656-61.

- Navsaria PH, Edu S, Nicol AJ : Civilian extraperitoneal rectal gunshot wounds : Surgical management made simpler. World J Surg. 2007 June; 31(6) : 1345-51.

- Gonzalez RP, Phelan H 3rd, Hassan M, Ellis CN, Rodning CB : Is fecal diversion necessary for nondestructive penetrating extraperitoneal rectal injuries ?

- J Trauma 2006; 61(4) :815-9

- Gonzalez RP, B.Turk : Surgical Options in Colorectal Injuries. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery 200 ; 91 :87-91.

- De Parades V, Zeiton JD, Atienza P : Cryptoglandular anal fistula. J Visc. Surg. 2010 Aug; 147(4) : 203-15.

Comments